Insights from DIWA’s work with the FBK Consortium

As one of the Philippines’ most economically significant crops, coconut is increasingly recognized in business and human rights conversations. But the path to responsible sourcing is far from straightforward. With the 4-year program officially finished, Louisse Borela, DIWA’s project manager for the Fund Against Child Labour (FBK) Consortium Coconut Project reflects on what we learned, encouraging coconut processors and buyers to use their influence in the supply chain to address real constraints and create space for local solutions.

Since 2021, DIWA has taken various approaches to understand and address salient labor and human rights risks in the Philippine coconut sector. From research and field-based assessments to supplier engagement and multi-stakeholder dialogue, our work has spanned several initiatives—each offering new perspectives on how change happens, and who makes it possible.

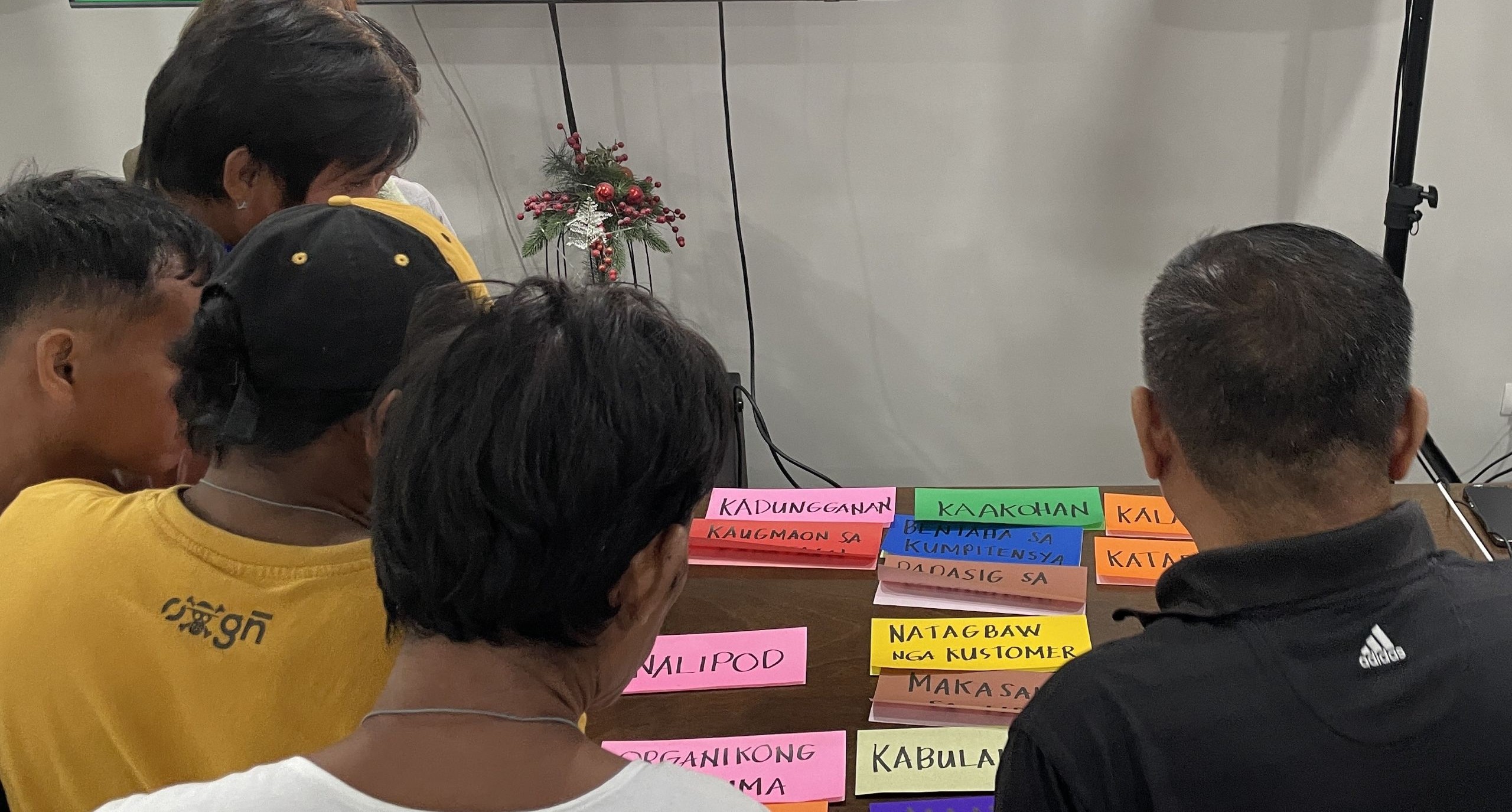

A central focus throughout has been child labor—a persistent and complex challenge. The FBK project piloted various approaches to address root causes of child labor. This included support to improve farming practices for higher household income, an area-based child labor monitoring system, and child rights due diligence and supplier engagement. In the Philippines, we might call this a bibingka approach, a term borrowed from a local rice delicacy and used to signify both top-down and bottom-up approaches.

For brands looking to build a sustainable coconut supply chain, DIWA’s work with the FBK project indicates that driving change in the sector requires that mills and processors are engaged as partners navigating real constraints. Conventional approaches to human rights due diligence often rely on audit-based models, certification schemes, or contractual clauses. However, in a context characterized by fragmentation and traditional methods of production, those tools may not go far enough. They may identify formal gaps at the top, but miss the informal dynamics—and human realities—at the bottom.

The Coconut Supply Chain: Fragmented and Traditionalist

The complexity of the coconut supply chain may bear resemblance to other agroforestry chains, yet it also exhibits distinct attributes. For instance, both coconut and cocoa represent fragmented global supply chains, underpinned by millions of smallholders, sharecroppers, and laborers. However, in contrast to cocoa, where farmer cooperatives frequently facilitate intermediation, the coconut sector demonstrates limited cooperative engagement in this capacity. While cooperatives and farmer organizations are present in the sector, the majority lack the operational capability to partake in trading activities. A substantial proportion of smallholders sell their produce to local traders. These relationships are often deeply established, personalized, and may involve intricate debt and credit arrangements, typically with minimal standardized documentation. Another differentiating characteristic lies in the nature of production and initial field-processing, which predominantly rely on traditional, non-mechanized methods at the farm level. The traditional smoke-drying method, a post-harvest technique practiced for generations, yields copra of variable quality, leading to reduced and less transparent pricing at the farm gate.

As the global demand for coconut products continues to grow, there’s a real opportunity to address risks in the sector and move towards long-term sustainability, modernization and decent work.

What We’re Hearing from Suppliers

Through our engagement with coconut suppliers—processors, traders, consolidators, and smallholder farmers and workers—we now have a clearer understanding of their perspectives and challenges. Despite differences, suppliers across the board are becoming more aware of human rights risks, particularly around child labor. But many express uncertainty about what they’re expected to do. Social responsibility and human rights due diligence are considered new concepts. Suppliers say they lack practical tools, clear guidance, or sustained support from buyers. Some fear that raising concerns or admitting gaps could lead to exclusion rather than assistance.

Still, the willingness to engage is there. We’ve seen suppliers participate in field assessments, share their sourcing practices openly, and express interest in strengthening systems—when approached with respect, partnership, and a recognition of their realities.

Moving Forward

The FBK project, as a multi-stakeholder initiative, provided DIWA the opportunity to work across an agricultural supply chain, including at farm-level. This required adapting our tools to guide various stakeholders in understanding and applying due diligence. We are looking forward to continuing this work through projects that similarly involve diverse stakeholders from farmer organizations to government agencies.

The FBK project has been a valuable platform for learning and testing approaches. As DIWA closes one chapter in its work in coconut through the project, we believe the lessons from this experience can—and must—inform how businesses engage with suppliers moving forward. Businesses can use their influence not only to set standards, but also to create space for locally grounded solutions.

The public project report with contributions from all Consortium members will be available later this year.